The Christ of the Breadlines, Fritz Eichenberg, Woodcut, 1951

For those Christians who worship a Holy God who cannot abide sin and whose righteousness demands punishment, today is a day to remember how God, the Father, inflicted all His anger on His Beloved Son, satisfying once and for all the debt of sin the human race has run up since we limped out of Eden.

I used to believe that myself. And, on a good day, I took comfort in it. I believed that my sins, even mine, were forgiven, and felt some peace, until I screwed up again.

As an old man, I have looked through enough microscopes and telescopes, stood at the foot of enough mountains, walked through enough forests, seen enough waves roll in, and held enough babies in my arms to change my definition of “Holy” from “Absolute Righteousness” to what Rudolf Otto was trying to express when he described the “Holy” as Mysterium et Tremendum:

“Mysterium” is the feeling I had in the mountains, at the seashore, and holding that new grandchild. It can’t be put into words.

“Tremendum” means what the hymn, “Were You There?,” is singing about:

“Sometimes, it causes me to tremble, tremble, tremble.”

This is what Moses felt when he stood before the burning bush. Isaiah felt this when he saw the Throne of God high and lifted up in the Temple. Mary felt this when the Angel Gabriel asked her to bear God’s Son.

It doesn’t matter whether you believe these stories are literally true or not. What matters is that they represent moments —moments I hope you have had—moments of awe that both humble you and fill your soul with a sense of your worth in the grand scheme of things.

The opposite of this feeling, these days, is consumerism. Consumerism only recognizes the value that can be rung up on a cash register, and throws away the things that no longer have value: toilet paper, laptops, and human beings. We are all immersed in it. Many of us struggle against it, but it can sometimes be overwhelming. The message is that our buying power measures our value. Those with more buying power are far more valuable than those with little or no buying power.

We Americans are currently ruled by two men who had the misfortune of being blessed with success by consumerism . One succeeded at making things that consumers will buy, and the other excels at selling things, even things that don’t exist. Consumerism has stunted our souls, so most of us buy what they sell—or at least don’t object to their pitch.

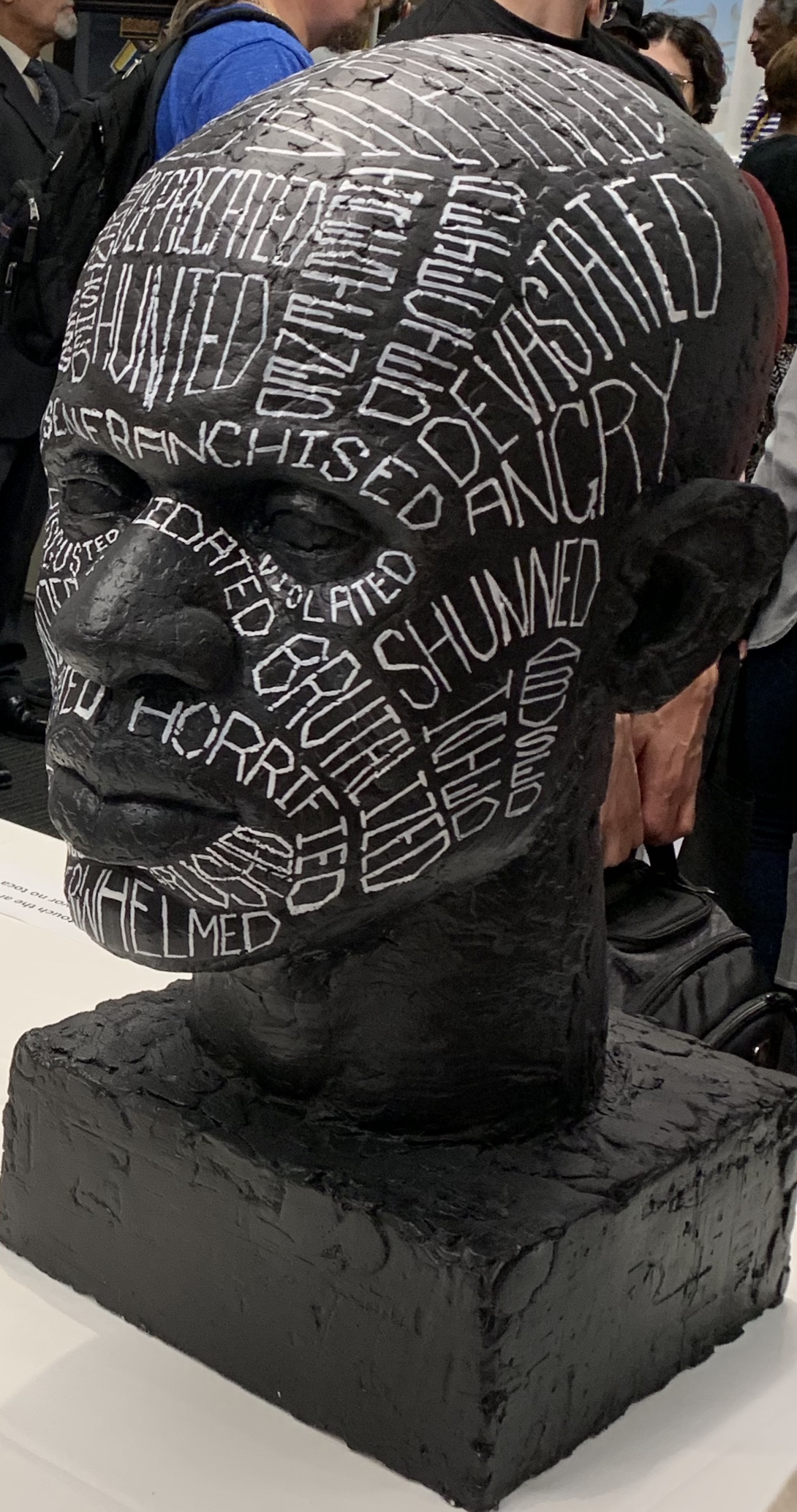

We are now beginning to see the ultimate evil that consumerism can drive us to — making a virtue of throwing away human beings

It is no accident that those who are now randomly firing “corrupt and lazy” scientists, weather forecasters, and park rangers and are advocating throwing away the elderly, the poor, the disabled, immigrants, and others they have deemed valueless, want us to forget that we did the same to Native Americans and Enslaved People. They don’t want us to see that their disparagement of DEI is a continuation of a pattern of cheating and exploiting women and people of color, while carving out some cushy positions for incompetent white guys.

According to some traditions, the place where Jesus was crucified was on top of Jerusalem’s trash heap. One of the things we remember on Good Friday is, “He took his place with sinners” . . . on the trash heap.

We always label the people we throw away “sinners” AKA criminals (read mentally ill, learning disabled, abused as children), shiftless people who can’t feed their kids even if they work three jobs, the disabled and old people who didn’t amass a fortune to support them and depend on Social Security instead. All of them drain money away from those of us who always want more. I am appalled at how well I understand that reasoning.

This Good Friday, Jesus takes his place with “gang members” (Guys with brown skin, Latino names, and wearing the wrong colored clothes) in a jungle prison in the ironically named country of El Salvador.

The only thing that will save Elon, Donald, MAGA, and me is to recover a belief in human beings as the image of God. To have an experience of the Holy, whether it manifests as a burning bush or a new grandbaby, a Heavenly Throne or a hug when we need it most and expect it least, an angel or an answer to our heart’s oldest question. We need the encounter with the Holy that Thomas Merton felt one day at the corner of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville.

He saw the faces of all the strangers passing him by and realized he loved them.

Then it was as if I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depths of their hearts where neither sin nor desire nor self-knowledge can reach, the core of their reality, the person that each one is in God’s eyes. If only they could all see themselves as they really are. If only we could see each other that way all the time. There would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed. . . . But this cannot be seen, only believed and ‘understood’ by a peculiar gift.

― Thomas Merton, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander