Even in the flat gray of the picture tube, she can make out the blue veins in her outer thighs, which somehow don’t seem possible, not yet. Not yet. She’s only forty-two, which, okay, when she was twelve seemed like one foot over the threshold into God’s waiting room, but now, living it, is an age that makes her feel no different than she always has. She’s twelve, she’s twenty-one, she’s thirty-three, she’s all the ages at the same time. But she isn’t aging. Not in her heart. Not in her mind’s eye.

Lehane, Dennis. Small Mercies (pp. 1-2). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. 2023

As I come up on my 75th birthday, I can identify with Mary Pat, the main character in Dennis Lahane’s new novel, even though varicose veins are one of the few signs of aging that I don’t have. But, that other thing — the feeling that the person I was at all those different ages is still there someplace inside of me — I get that. And, I’ve been thinking about those moments a lot recently.

When you get to be my age, you realize that nothing is permanent. I have a vivid memory of standing at the foot of one of the world’s tallest buildings and thinking about the effort it took to build something that massive. I wondered what could possibly bring down something that big? It was the night before our son, Jim, and his wife, Rachel, would be married in the chapel of Hebrew Union College, a few blocks away. The building was the World Trade Center and almost everyone in my family was staying at the Marriott in the lower floors that night, August 11,2001.

Nothing lasts forever. It’s not just big buildings that come down, but giant corporations (Pontiac, A & P), venerable institutions (your church may be one of them), and social norms (a marijuana store just opened five blocks from where I’m sitting.)

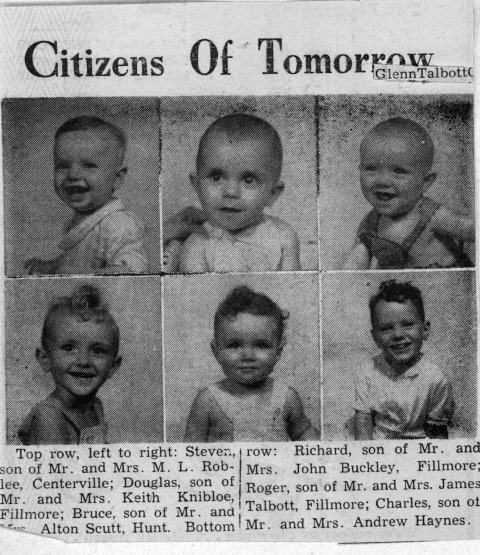

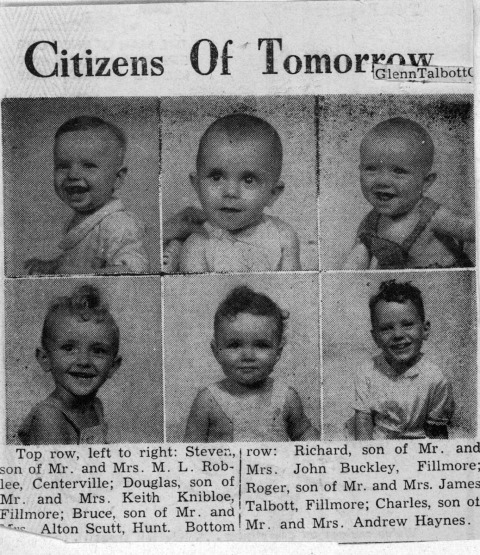

Most of the time, the changes are so gradual that we hardly notice. But then, it hits us. On their 50th anniversary I looked through my parents’ wedding guest register. I had known most of the people who signed, and I realized, with a start, that the majority of them: my grandparents, their brothers and sisters, and close friends, were all gone — as were several members of Mom’s and Dad’s generation. That was twenty-six years ago. Now my parents’ generation is all gone, too.

It feels like my life and the lives of everyone I know and love are like leaves in the Niagara River. We float along together for awhile and pick up speed as we get closer to the falls. That truth can be terrifying.

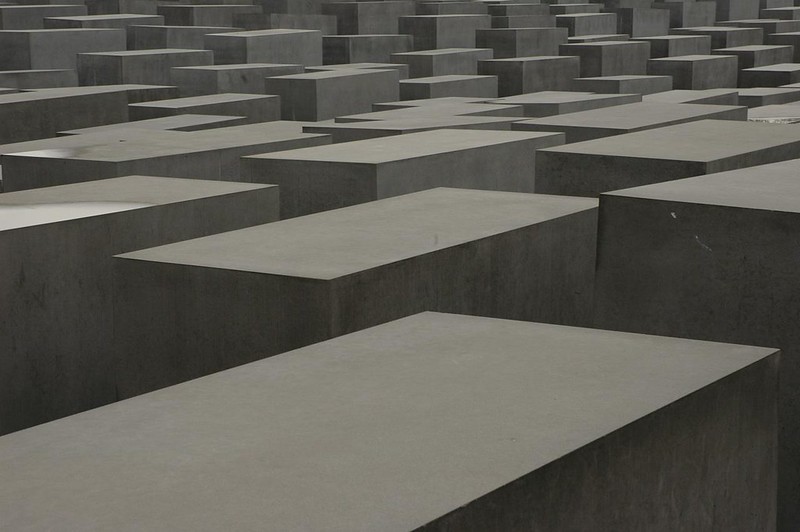

But, there is another way to look at life. Instead of a river, the times of our lives can look like a layer cake, or like an archaeological site:

https://www.southalabama.edu/org/archaeology/news/stratigraphy.html

Like Mary Pat, I have caught my reflection and seen, not just my balding head, but myself as a 55-year-old senior pastor, a young husband and father, a teen-ager whose pants’ inseams were longer than my waist size, even the pre-schooler blowing dandelions on a summer’s day.

In some meaningful way, the person I was, and the people I knew, and even the things I did all seem to be preserved in those layers of time.

And maybe they are. I was recently introduced to the Buddha’s Five Remembrances:

- I am subject to aging. There is no way to avoid aging.

- I am subject to ill health. There is no way to avoid illness.

- I am going to die. There is no way to avoid death.

- Everyone and everything that I love will change, and I will be separated from them.

- My only true possessions are my actions, and I cannot escape their consequences.

Yes, four of those remembrances are about change. I can’t hang on to my youth, my health, my life, or my loved ones, but my past experiences and actions are different. They continue to be a part of my life.

I miss our son, Matt, who died last summer. I can’t call him on the phone. He won’t be around to celebrate my 75th birthday. But, in the layers of my life, he is still the tiny infant we brought home from the hospital, the toddler learning to walk, the teenager whose comments made his younger brother laugh, the young man introducing us to the woman he married, the father with two delightful teens of his own.

These memories don’t tempt me to live in the past. They remind me that the past lives in me.

As I look back, my life looks like a layer cake. The more layers, the richer my life is. Every decade, year, day, hour, moment, is a layer. I am learning late that what I decide to do with this day and hour makes a permanent difference.

As one of the wisest survivors of the Holocaust said:

Any hour whose demands we do not fulfill, or fulfill halfheartedly, this hour is forfeited, forfeited “for all eternity.” Conversely, what we achieve by seizing the moment is, once and for all, rescued into reality, into a reality in which it is only apparently “canceled out” by becoming the past. In truth, it has actually been preserved, in the sense of being kept safe. Having been is in this sense perhaps even the safest form of being. The “being,” the reality that we have rescued into the past in this way, can no longer be harmed by transitoriness.

Victor Frankl, Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything