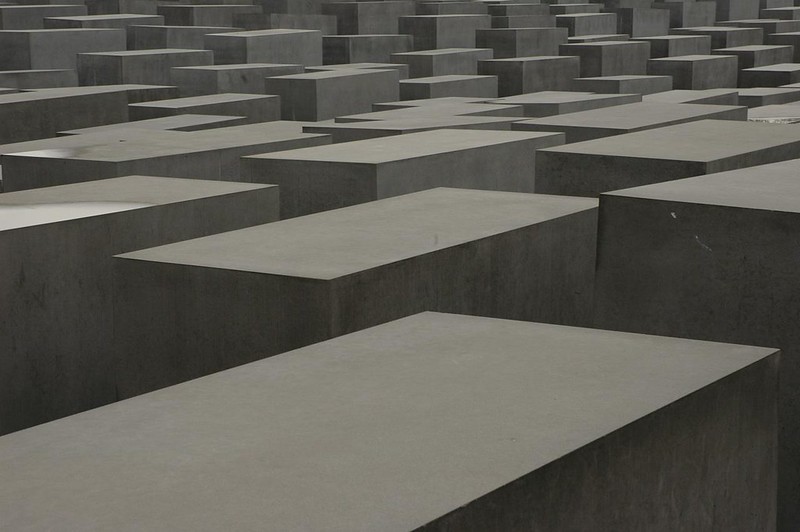

Photo by Arthur Edelmans on Unsplash

The word “grandpaphone” came to me as I woke from a dream.

In the dream, I was at a family reunion. Some youngsters were showing me a trick that they learned. They poured a liquid on an old LP record. It flattened the grooves, making the surface shiny and smooth. I said they shouldn’t do that and explained what the grooves were for. I wanted to tell them about playing my grandmother’s old wind-up gramophone as a boy. It played recordings on cylinders instead of disks. But first, I wanted to figure out whose grandkids these were. They must belong to one of my siblings. However, they seemed not to know who I was talking about when I named my brother and sisters.

I realized the meaning of this dream in what my son calls “Ha-Ha time” (half asleep and half awake).

The children who erase the LP and do not remember my generation’s names will be my grandchildren’s grandchildren. I don’t know all the first names of my sixteen great-great-grandparents. Do you know yours?

Unless your ancestors are the kind of people recorded in history books or you are an obsessive-compulsive genealogist, you are unlikely to know much about that generation.

The dream confronted me with an aspect of mortality that may be even more profound than the eventual death of my body — the erasure of the fact that I ever lived.

I heard this hymn playing in the background:

Time, like an ever-rolling stream,

Isaac Watts revised by Brian Wren

bears all who breathe away,

they fly, forgotten, as a dream

dies in the dawning day.

That was when I woke up, and the word “grandpaphone” came to me. A grandpaphone picks up and plays the vibrations of the ancestors through the generations.

That is the best I can hope for. My efforts to become immortal aren’t bearing much fruit.

If my descendants have an enormous trust fund, it won’t bear my name, and they won’t have other reminders of my existence.

I did publish a book of sermons, but it went out of print in the 1990s. The paper in the copies I have on my shelves is already turning yellow.

I can count on appearing in the histories of the churches I served, but I fear that most of those churches won’t make it past the middle of this century.

The dream was calling me to recognize a truth my culture ignores –the importance of ancestors.

My particular Christian tradition has been guilty of looking down its nose at what it calls “ancestor worship.” So we reduce one of the Ten Commandments: “Honor your father and your mother, that your days may be long upon the earth,” to handing out corsages on Mother’s Day.

Rabbi Abraham Heschel was once asked what this commandment meant for people who had been abused or abandoned by their parents. Rabbi Heschel said the commandment does not require us to pretend that bad behavior is honorable. What it does command us to do is to have a reverence for the mystery of our own existence. Our parents, their parents, and all our ancestors are the symbols of that mystery.

Our ancestors do, indeed, represent a mystery: the mystery of who we are, how we got here, and, maybe, where we are going.

I was lucky to know all four of my grandparents, one of my great-grandmothers, and a step-great-grandmother. Some people come from family lines full of the kind of people who get biographies written about them — or at least an article in Wikipedia. Some people don’t even know the names of the two people who made them. But we all have this in common: a family tree that doubles in size with every generation: four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, sixteen great-great-grandparents — you can do the math. We don’t often realize that if even one of our 128 ancestors seven generations ago had not “come through,” as it were, you and I would not be here.

Perhaps your reaction is, “I’m just a random set of genes that came together to win the life lottery.”

Or maybe you think like my grandchildren. Once, when all four of them were together, I told them how my 15-year-old self got up the nerve to reach out for their grandmother’s hand, and she let me hold it. After telling that story, I asked, “Are you here because I reached for her hand? Or did I reach for her hand because you are supposed to be here?”

They all agreed that their inevitable future existence was the reason I crushed on their grandmother.

Whatever you think—and I admit there are days when I think my life is a lottery ticket and days when I think my life is inevitable—just thinking about it should fill us with reverence for the mystery of our existence.

You can create a very simple daily discipline of remembering your parents and their parents, grandparents, and ancestors and bowing in gratitude, thanking them for the gift of life. Since I have added that to my morning routine, I feel a reverence for life that I haven’t felt before.

I think I am playing the grandpaphone.