— Demonstration supporting Sammy’s Law, March 22, 2024. Photo: Roger Talbott

This is the week when Christians recall the passion and death of Jesus. On Thursday, we have a service to remember his last supper. On Friday, we often have long services in the afternoon that recall the seven things he said on the cross or the 12 events that happened on the way to the cross.

All these are in preparation for the joyous celebration of Christ’s resurrection on Easter Day.

Some churches also have a service of Tenebrae — a word that means “darkness.” The service consists of lamentations from the Psalms and the prophets. No one preaches. If there is music, it is also the music of lament and grief — think, “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord.” Periodically, a candle at the front of the church is extinguished, and the church grows so dark it is hard to see anything but the candles.

In the end, only one large candle remains lit and it is removed from the sanctuary. The congregation sits in silence. Then there is a loud noise. Last night, someone beat on an unseen kettle drum. The large candle is returned to the front of the church, a symbol of St. John’s words, “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has never put it out.”

When I used to lead Tenebrae services in the suburban church I pastored when our sons were growing up, our son Matt helped me by making the loud noise at the end of the service. He created a loud, hollow noise that sounded like a door slamming shut on your tomb.

As an adult, Matt sometimes attended a Tenebrae service even if he didn’t attend church on Easter morning. He said, “It is the world’s best horror show.”

As I recited lamentations in my church’s Tenebrae service this year, I remembered how all of us who loved Matt felt when he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and watched over the next ten terrible weeks as he slowly wasted away in front of us, even as the light of his love for life and his family fought back against the darkness.

The feeling we had, like the feeling the followers of Jesus must have had in the last few hours of his life, was anguish.

It is the same feeling I have had for the last six months about Israel and Gaza.

I have Jewish family and friends for whom Israel’s national security represents a kind of psychological safety net in a world that periodically decides to blame Jews for everything. The brutal attack on October 7-8 poked a hole in that safety net. Many of them see the net being further degraded as Israel’s short-term military objectives risk the long-term safety of all the world’s Jews.

As what might have been a just war has become just war, my friends and friends of friends who are Muslim, Arabic Christians, and people whose skin doesn’t match the paint samples Americans arbitrarily call “White” see our country’s support of Israel (now waning) as a clear indication that some lives matter more than others.

The great temptation is to feel nothing. After all, I can’t do anything about it. It is the way of the world. As one of my pastors said last Sunday, most of the people involved in Jesus’ crucifixion treated it the way we Americans treat mass shootings. It was just another day.

His Sunday sermon, the Tenebrae service last night, Holy Thursday, and Good Friday remind me if I am to remain whole and human in this cruel world, I am called to feel anguish.

I Googled “anguish” and found this:

“Anguish is often referred to as emotional distress or pain, and it can encompass several different emotions, such as trauma, grief, sorrow, fear, and anxiety. It’s a reasonable, typical, and sometimes even a rational response to a horrible situation.”

Betterhealth.com

It isn’t easy to choose to feel distress and pain. No one can do it all the time, as the exhausted caregivers of dying loved ones know all too well. Yet we also know that shutting those feelings out entirely makes us less than human.

We need rituals and seasons that bring us back to our anguish.

In the last few years, I’ve been fascinated by how people who never go to church, especially young people, show up for Ash Wednesday. Having ashes applied to your forehead while hearing “Remember you are dust” is as grim a ritual as there is in Christianity’s toolbox. Yet, if a clergy person is willing to stand in a public place and perform that ritual, people will line up for it, showing that it reaches something that happy, clappy weekly “celebrations” do not. It helps us get in touch with the anguish of life itself. I suspect that if there were some way to take Tenebrae out into the streets, people would line up for that, too.

I experience the same “vibe” when I attend Yom Kippur services at Malkhut, the Jewish spiritual community my daughter-in-law, Rabbi Rachel Goldenberg, has formed here in Western Queens, and hear my son, Jim, chant in Hebrew alphabetical order the names of the sins we all commit. (You can taste that vibe by listening to Leonard Cohen sing “Who by Fire.”) I suspect that my Muslim friends who are observing Ramadan are getting in touch with the same feelings.

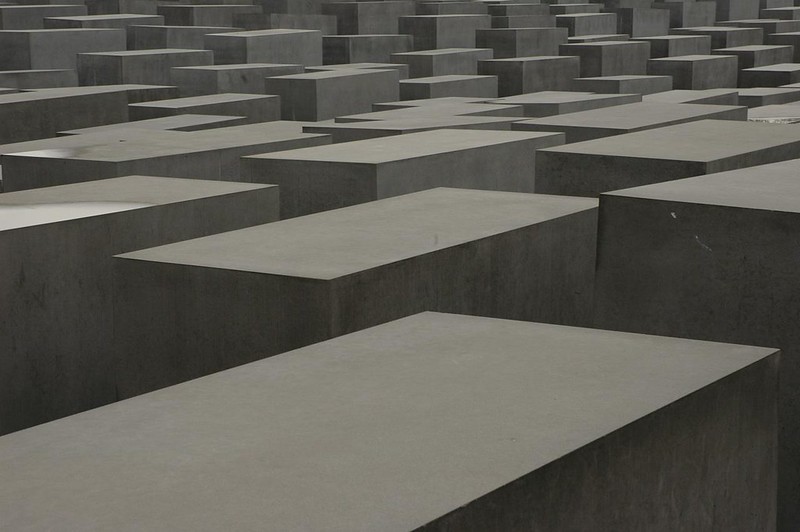

I have recently seen the importance of secular rituals of lamentation, too. I have attended demonstrations led by Jews and Muslims demanding a ceasefire in Gaza. I recently marched with neighbors who are demanding a radical change in New York State law — to give New York City the right to set its own speed limits — a week after another child had been run over in Queens. All of them are acts of communal anguish and lament.

As the Old Testament scholar Walter Bruggemann has repeatedly pointed out, lamentation is prophetic. It expresses humanity’s resistance to the Powers that Be, who insist cruelty and death are necessary. Living in this world without anguish means caving to the Powers that are trying to squeeze us into their image.

Jesus once said, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.” We find comfort because we are not alone; we are part of the human race made in the image of God, who often weeps over us.

This is part of a larger project on the Beatitudes. I would appreciate any comments you would like to share.