“Is Jacquie there?”

This question — the very first words I heard after I picked up the phone – told me that my mother-in-law was calling. It was back in the day when people paid for long-distance calls by the minute and she didn’t have the pennies to spare on chit-chatting with her son-in-law. I got it. I also suspected that her feelings about me were . . . complicated.

Over the years, however, we forged a relationship.

She and I were both early risers. When she would come to visit, we would sit together in the kitchen drinking our first cup of coffee of the day and we would talk about the three people we both loved with all our hearts. Not long before she was diagnosed with the cancer that would take her life, she sent me a Father’s Day card on which she listed all the good qualities she saw in me. It was an affirmation I still cling to.

My love for her daughter and her love for our sons transformed a difficult relationship into a kind of friendship. She died more than 30 years ago, and I still miss her.

We are tempted to see the world in binaries. The most fundamental being “I” on the one hand and anything else, including “You,” on the other. And when it is just “you” and “me,” we either try to absorb each other, or push each other away.

The first page of the Bible says God made it that way. On the first day God creates the first binary: day and night. On the second day, God separates earth from sky. I never noticed until someone pointed it out to me recently, that God does not bless these first two days. These binaries are static; in opposition to each other. But, on the third day, God separates the land from the sea and these binaries start producing a third thing: Life. That is when God starts calling the Creation “good.”

This is the mystery of Three.

The ancient alchemists were focused on transformation. How does one thing turn into another? The alchemists knew that one substance all by itself was inert. Two substances, like oil and water, would never really come together. But, add a third thing — a coagulant — and they would form something new.

The alchemists wanted to turn lead into gold. But there is also an alchemy that makes a distrustful stranger, a competitor, even an enemy, into a friend if you add a third thing. According to the mystics, that third thing is either Love or Fear. Both of them can turn enemies into friends.

You know the saying: “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Fear seems to be the basis of everything from family dysfunctions to international relations.

We create communities based on fear, not because we are bad people, but because we have evolved to sense threats to our existence. And we have learned that we have a greater chance to survive those threats if we band together. The members of NATO have many competing interests, but they recognize that Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine implies a threat to each of them. That is not an irrational fear.

However, alliances based on fear can survive only as long as the threat persists. Indeed, NATO was on the verge of falling apart as Russia became more integrated into the global community.

Lacking any genuine threat, human communities are tempted to manufacture fears in order to hold themselves together. Just think of the ways our political parties energized their bases to get out the vote two months ago. Sadly, it works. And it is easy to do.

But, there is another image of the “Three” that appears in front of churches during this short season of 12 days called “Christmastide” — a mother, a father, and a baby. You don’t have to be Christian or even religious to understand that this is a symbol of Love with a capital “L.”

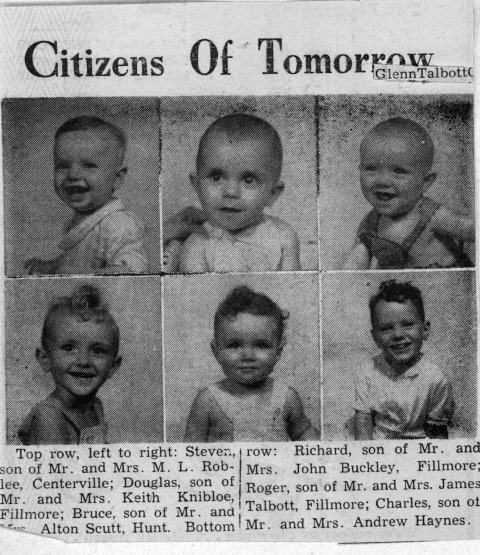

It is a reminder that human beings can and do forge relationships based on their mutual love for some other person or thing. At weddings we laugh and dance with each other. At funerals we cry and hug each other. We connect with complete strangers and create community because we all love the same people. People who love growing flowers form garden clubs. People who care about the poor form the crew at the hunger center.

While the headlines focus on the building up of international alliances based on the fear of Russia’s military aggression and China’s economic hegemony, tens of thousands of individuals and hundreds of organizations are banding together rescue people from poverty, hunger, and disease in ways that seldom appear on Fox News or CNN. These groups are often coalitions of people from many nations and of different faiths.

When people band together to fight a third party they often feel a sense of belonging and purpose. But, ultimately, those relationships are destructive.

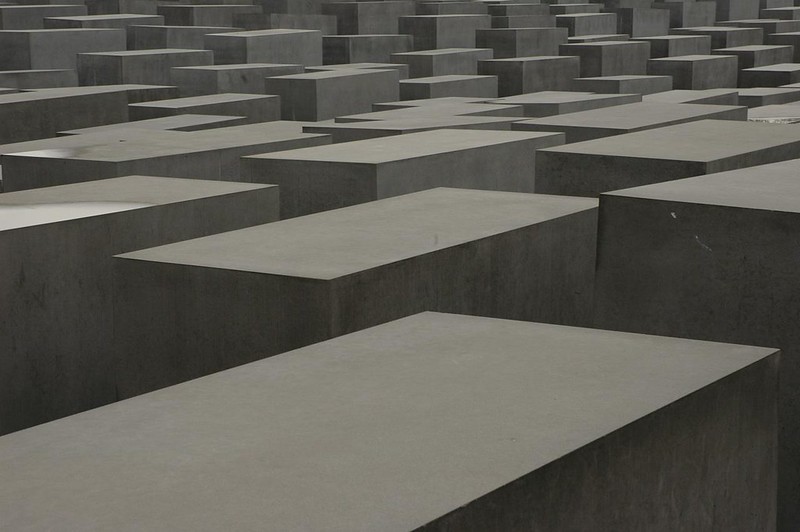

In his play, No Exit, the philosopher, Jean Paul Sartre, created a vision of Hell as a cell containing three people who would spend eternity creating shifting alliances based on their fearful hatred of each other. It is a hell in which a lot of us live every day. Fear encourages lying and betrayal. It creates a “brood of vipers” as one biblical prophet called them.

In contrast, the relationships forged on mutual love are usually marked by deep loyalty and faithfulness that persist over years. These relationships encourage honesty and integrity in those who enter them. And they are creative.

It does not have to be a child, but it does have to be something that calls out the best in people — something they love and serve with all their hearts, and also makes them want what is best for each other.

Again, the Holy Family is an obvious symbol of this mystery and Christians have spun it out into the doctrine of the “Trinity.” I would assert that, in the conversation between the great Wisdom Traditions of the world, Christianity’s main contribution may be its insight that this Mystery of Three is what puts the “uni” in “Universe.” *

As a teacher of mine who was well-versed in both theology and science pointed out: planets and solar systems and galaxies are held together by gravity. Atoms and molecules are held together by atomic forces. The universe is held together by mutual attraction — the universe is held together by love.

As the New Year begins, consider the Holy Family and ask yourself These questions:

- Which relationships do you have that are based on fear?

- Which are based on love?

- Which ones are most satisfying?

- Which call out the best in you?

- Which ones will you work on?

And, If you would like to transform a relationship ask:

- What do both of us love?

Do you have any stories of transforming a relationship? I’d be curious to hear them.

The Feast of the Holy Family, January 1, 2023

*(Although, sadly, Christians have spent almost 2,000 years fearing and hating people who understand this mystery even slightly differently from the way they understand it.)