If you are in the Third Half of Life, you are probably grieving.

The grief may be passing through your life like a thunderstorm, or sitting over you like long days of rain. Or it may, for now, be part of the climate of your life.

You may or may not believe that global climate change is real, but I bet you have noticed in this Third Half of Life that the emotional climate of your life is not as bright and carefree as it once was. Your days, no matter how bright, may be tinged with sadness, the warmest of hugs and most intimate conversations may be accompanied by a chill.

This does not mean you are morbid or unhappy, it just means that you know in your bones that things — and people — can end.

As with global climate change, ignoring these changes only makes things worse. Acknowledging the fact that grief is part of the Third Half of Life enables us to savor the sunlight and find meaning even in the rainiest of days. Grief can make us more human, if we don’t avoid the work that goes with it.

My personal experience with grief has been blessedly ordinary. Like almost everyone my age, I have seen both my grandparents’ and parents’ generation pass away. I have been spared, so far, the loss of my beloved, or any of our younger family members. My only credential is that I have watched people grieve for over half a century. More than that, I have grieved with them.

I was not many years into the ministry before I realized that part of the psychic load of being a pastor was that I was grieving all the time.

Believe it or not, I loved my parishioners. I had to. It was the only way I could stand most of them. Given all my faults, I must have been loved by them in return. So, I grieved when they died. And, I did not have to be an empath to feel the deep griefs so many of them carried in their hearts. Not that it was a constant topic of conversation, but there would be moments when:

- A widow would recall the life she shared with the man she loved.

- A mother would recall a child who died before I was born.

- A man would mention that he still missed a cat that he had to euthanize a year ago.

- Someone would talk about father who died when he or she was fourteen.

These were the vibes that people emanated whether they told their stories or not.

Most of all, I have had a ringside seat with people when they lost loved ones. I sometimes had to bring them the news myself. As we prepared for the funeral, I coaxed them to describe their loved one. I would follow up with them in visits weeks and months afterward.

That work helped me develop some deep convictions about grief — especially what the work of grief is. Most of that work is subconscious — it is soul work. It cannot be described in words.

A colleague of mine, the pastor of a neighboring church, pointed to this inner work when he described how he handled his brother’s sudden death in an auto accident. The two of them were a about a year apart in age. They had been close all their lives. So, my colleague felt the loss of his brother very deeply. He said that he mowed his lawn almost every day for months after the funeral. Pushing his mower back and forth over his large lawn gave him the space to do that inner work that no one can describe.

However, there are four things we do when we grieve that can be described imperfectly, haltingly, because we tread on the edge of mystery. These four things are:

- We remember

- We make sense out of our memories

- We forgive

- We decide what we believe about life, death, and life-after-death.

These are not “stages of grief.” You can find lots of books on that subject. This is the work we do for everyone we love and lose. It never really ends. Right this moment, you are doing that work for people who have been dead longer than a lot of the adults you know have been alive.

In the next few weeks, I am going to go into this work in more detail.

It would help me to hear from you about how you have handled the grief in your life.

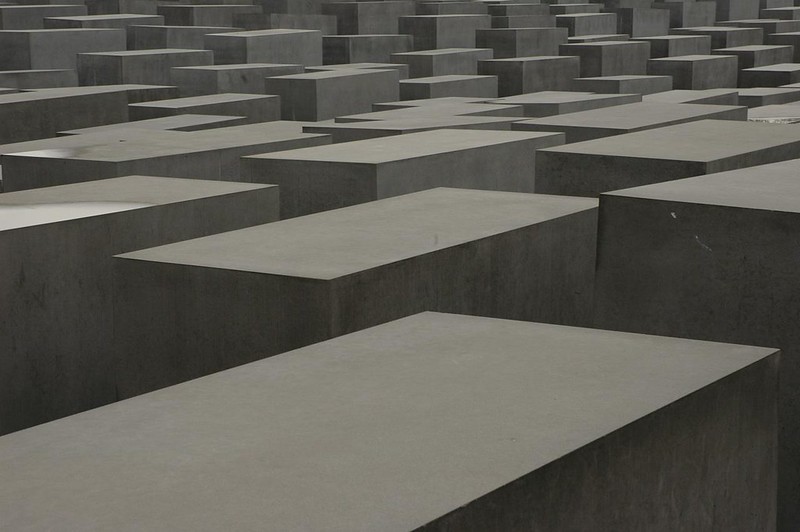

Image credit: Raul Diaz, Berlin Germany, Holocaust Memorial https://www.flickr.com/photos/radzfoto/2621999611/in/dateposted/